- Home

- Malorie Blackman

Love Hurts Page 4

Love Hurts Read online

Page 4

Charlie leaned in, and she leaned to meet him. His mouth found hers, and her thoughts flew through her, as loud and raucous as magpies. My first kiss. I am eighteen, and this is my first kiss, unless I count Jake What’s-His-Name in eighth grade, which I don’t. Because this is . . . different. So different.

And then her thoughts dissolved into lips. Breath. A soft sigh, a shifting thigh. She gave herself over to Charlie and the night and the world, full of mysteries. She allowed herself to just be.

More than.

Charlie wanted to see Wren again. She was all he could think about – kissing her, touching her, being with her – and he wanted to do it again. Right away.

He called her the morning after P.G.’s party.

‘Charlie?’ she said when she answered, and his heart jumped.

‘Hey,’ he said.

‘Hey.’

‘How are you?’

‘I’m good. How are you?’

‘I’m good,’ he said. His conversation skills sucked. He couldn’t talk worth a damn, but last night he kissed her, and she kissed him back. So, yeah. He was very, very good.

‘I was wondering whether you’d like to do something,’ he said abruptly. ‘I’d like to see you.’

‘Today?’

‘I could grab some sandwiches if you want. I could come pick you up. I was thinking we could go on a picnic, if that sounded like something you might like. Is that . . . something you might like?’

‘Um, sure,’ she said.

‘Great. Awesome. Great.’

She giggled. ‘What time?’

‘Now,’ he pronounced, and she giggled again. He was too thrilled to be embarrassed. ‘I’ll be at your house in fifteen minutes. Hey – are you afraid of heights?’

‘Of heights? Why?’

‘No reason. See you soon.’

He took her to a spot along the Chattahoochee River where the sky was wide and blue. Trees lined the bank, and birds sang as they flitted from branch to branch. The water was brown, but it glinted and turned to gold when it splashed over the moss-covered rocks.

Charlie drove here when he needed to think. Until today, he’d always come alone.

‘It’s beautiful,’ Wren said after climbing out of the car. She was wearing a sundress, or some sort of dress, and it swished against her thighs. She had on cowboy boots, and her hair was pulled into a ponytail. She was beautiful.

‘Come on,’ he said, almost reaching for her hand. He didn’t, and he cursed himself.

He headed up the trail. She followed.

‘Do you go hiking a lot?’ she asked.

‘Um, what do you mean by hiking? You mean like what we’re doing now?’

‘I guess,’ she said. ‘Being outside – is that something you like?’

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘Yeah. When I was a kid, I was inside a lot, so yeah, I’d rather be outside if I can.’ He glanced back at her. Her skin was smooth and creamy. When she stepped over a log, he caught a glimpse of the paler skin of her inner thigh. There, and then gone.

Take her hand, he told himself, and this time he did.

‘And you?’ he said. They started back up the trail. ‘Do you like being outside?’

‘Mmm-hmm,’ she said. ‘Especially the ocean. Oh my gosh, I love the ocean. I love catching waves and getting all salty, and hungry – I get so hungry after swimming in the ocean – and then flopping down all wet on my towel and letting the sun soak in.’

She made a small sound that was almost a moan, and Charlie’s cock stirred. Wet and warm and salty? Damn. Everything she said, she said so innocently, and yet she drove him so crazy. She drove him more crazy because she was so innocent.

Discreetly, he tugged at his jeans. ‘I’ve never been.’

‘To the ocean? You’ve never been to the ocean?’

He shook his head. ‘One day.’

‘Oh, Charlie, you have to,’ she told him. ‘If you like being outside – wow. You will love the ocean. It makes you feel so . . . I don’t know. Small, but not in a bad way. Small because you realize you’re part of something bigger. It gets you out of your head, if that makes sense.’

She almost tripped on a root. Charlie caught her.

‘You all right?’ he said.

‘Yeah, thanks,’ she said, looking embarrassed. She let go of his hand. He wished she hadn’t. Then, after a moment’s hesitation, she looped her arm through his, and he was elated. Her breast brushed against him. She brought her other hand across her body and rested it on his biceps, above their linked elbows.

She smiled shyly up at him. ‘Is that okay? I’m not making it hard for you to walk or anything?’

She was, but not in the way she meant. Yes, it was okay.

‘Do you think that life has patterns in it?’ she asked.

‘Patterns? Like what?’

She exhaled in a sweet way. ‘Like, in a non-random way. Like, do things happen for a reason?’

‘Hmm,’ Charlie said. Science and math were subjects he did well at, and in general, he was more comfortable with ideas that could be expressed in formulas than ideas that couldn’t fully be explained. Then again, scientific theories started with the seed of an unexplained idea. Mathematical formulas often described phenomena that couldn’t be physically verified.

‘I’m not sure,’ he said. ‘I’m certainly not willing to discount it.’

‘Me either,’ she said. ‘And, okay, this is going to sound silly, but when you called me this morning . . .’

‘Yeah?’

‘Well, when I heard your voice I felt . . .’

He waited.

She blushed and squeezed his arm, and he realized that she wasn’t going to answer. But he thought that if the world was layered with meaning, then she was the evidence, right here. She was the mystery and the explanation, both.

They reached the place in the trail Charlie had been waiting for, and he gestured with his chin at what lay ahead.

‘Hey,’ he said. ‘Take a look.’

She caught her lower lip between her teeth. ‘Whoa.’

‘Yeah,’ Charlie said.

‘How did I not know this was here?’ Wren said. ‘How have I never been here before?’

‘Let’s go up,’ Charlie said, leading her toward the embankment. Above them stood a decaying railroad bridge that was built probably a hundred years ago. The wooden support beams stretched like a row of giant As into the clouds. The steel rails that trains once rode on were long gone, but the underlying tracks remained.

At first, Wren kept her arm linked in his as they climbed. Then the dirt grew loose, and she had to use her hands for balance and to clutch at branches. Charlie, behind her, glimpsed the curve of her ass and a flash of panties.

He took several big steps to pass her. From the top of the rise, he extended his hand.

‘Oh wow,’ she said, breathing hard. ‘We’re as high as the treetops.’

‘Let’s go out,’ he said. He squeezed her hand. ‘You want to go out?’

‘To the middle of the bridge?’

‘Yeah, come on.’

Two rotting wooden tracks, each approximately three feet wide, stretched across the gulley below. They were sturdy enough to walk on – Charlie would never put Wren in danger – but the ground dipped steeply away several yards past the top of the embankment. Walking along them was like walking along a wide balance beam, only much higher off the ground. Charlie went first and kept Wren’s hand in his.

FROM

IF I STAY

BY

GAYLE FORMAN

‘Have you ever heard of this Yo-Yo Ma dude?’ Adam asked me. It was the spring of my sophomore year, which was his junior year. By then, Adam had been watching me practice in the music wing for several months. Our school was one of those progressive ones that always got written up in national magazines because of its emphasis on the arts. We did get a lot of free periods to paint in the studio or practice music. I spent mine in the soundproof booths of the music wing. Adam was there a lot, to

o, playing guitar. Not the electric guitar he played in his band. Just acoustic melodies.

I rolled my eyes. ‘Everyone’s heard of Yo-Yo Ma.’

Adam grinned. I noticed for the first time that his smile was lopsided, his mouth sloping up on one side. He hooked his ringed thumb out toward the quad. ‘I don’t think you’ll find five people out there who’ve heard of Yo-Yo Ma. And by the way, what kind of name is that? Is it ghetto or something? Yo Mama?’

‘It’s Chinese.’

Adam shook his head and laughed. ‘I know plenty of Chinese people. They have names like Wei Chin. Or Lee something. Not Yo-Yo Ma.’

‘You cannot be blaspheming the master,’ I said. But then I laughed in spite of myself. It had taken me a few months to believe that Adam wasn’t taking the piss out of me, and after that we’d started having these little conversations in the corridor.

Still, his attention baffled me. It wasn’t that Adam was such a popular guy. He wasn’t a jock or a most-likely-to-succeed sort. But he was cool. Cool in that he played in a band with people who went to the college in town. Cool in that he had his own rocker-ish style, procured from thrift stores and garage sales, not from Urban Outfitters knockoffs. Cool in that he seemed totally happy to sit in the lunchroom absorbed in a book, not just pretending to read because he didn’t have anywhere to sit or anyone to sit with. That wasn’t the case at all. He had a small group of friends and a large group of admirers.

And it wasn’t like I was a dork, either. I had friends and a best friend to sit with at lunch. I had other good friends at the music conservatory camp I went to in the summer. People liked me well enough, but they also didn’t really know me. I was quiet in class. I didn’t raise my hand a lot or sass the teachers. And I was busy, much of my time spent practicing or playing in a string quartet or taking theory classes at the community college. Kids were nice enough to me, but they tended to treat me as if I were a grown-up. Another teacher. And you don’t flirt with your teachers.

‘What would you say if I said I had tickets to the master?’ Adam asked me, a glint in his eyes.

‘Shut up. You do not,’ I said, shoving him a little harder than I’d meant to.

Adam pretended to fall against the glass wall. Then he dusted himself off. ‘I do. At the Schnitzle place in Portland.’

‘It’s the Arlene Schnitzer Hall. It’s part of the Symphony.’

‘That’s the place. I got tickets. A pair. You interested?’

‘Are you serious? Yes! I was dying to go but they’re like eighty dollars each. Wait, how did you get tickets?’

‘A friend of the family gave them to my parents, but they can’t go. It’s no big thing,’ Adam said quickly. ‘Anyhow, it’s Friday night. If you want, I’ll pick you up at five-thirty and we’ll drive to Portland together.’

‘OK,’ I said, like it was the most natural thing.

By Friday afternoon, though, I was more jittery than when I’d inadvertently drunk a whole pot of Dad’s tar-strong coffee while studying for final exams last winter.

It wasn’t Adam making me nervous. I’d grown comfortable enough around him by now. It was the uncertainty. What was this, exactly? A date? A friendly favor? An act of charity? I didn’t like being on soft ground any more than I liked fumbling my way through a new movement. That’s why I practiced so much, so I could rush myself on solid ground and then work out the details from there.

I changed my clothes about six times. Teddy, a kindergartner back then, sat in my bedroom, pulling the Calvin and Hobbes books down from shelves and pretending to read them. He cracked himself up, though I wasn’t sure whether it was Calvin’s high jinks or my own making him so goofy.

Mom popped her head in to check on my progress. ‘He’s just a guy, Mia,’ she said when she saw me getting worked up.

‘Yeah, but he’s just the first guy I’ve ever gone on a maybe-date with,’ I said. ‘So I don’t know whether to wear date clothes or symphony clothes – do people here even dress up for that kind of thing? Or should I just keep it casual, in case it’s not a date?’

‘Just wear something you feel good in,’ she suggested. ‘That way you’re covered.’ I’m sure Mom would’ve pulled out all the stops had she been me. In the pictures of her and Dad from the early days, she looked like a cross between a 1930s siren and a biker chick, with her pixie haircut, her big blue eyes coated in kohl eyeliner, and her rail-thin body always ensconced in some sexy get-up, like a lacy vintage camisole paired with skintight leather pants.

I sighed. I wished I could be so ballsy. In the end, I chose a long black skirt and a maroon short-sleeved sweater. Plain and simple. My trademark, I guess.

When Adam showed up in a sharkskin suit and Creepers (an ensemble that wholly impressed Dad), I realized that this really was a date. Of course, Adam would choose to dress up for the symphony and a 1960s sharkskin suit could’ve just been his cool take on formal, but I knew there was more to it than that. He seemed nervous as he shook hands with my dad and told him that he had his band’s old CDs. ‘To use as coasters, I hope,’ Dad said. Adam looked surprised, unused to the parent being more sarcastic than the child, I imagine.

‘Don’t you kids get too crazy. Bad injuries at the last Yo-Yo Ma mosh pit,’ Mom called as we walked down the lawn.

‘Your parents are so cool,’ Adam said, opening the car door for me.

‘I know,’ I replied.

We drove to Portland, making small talk. Adam played me snippets of bands he liked, a Swedish pop trio that sounded monotonous but then some Icelandic art band that was quite beautiful. We got a little lost downtown and made it to the concert hall with only a few minutes to spare.

Our seats were in the balcony. Nosebleeds. But you don’t go to Yo-Yo Ma for the view, and the sound was incredible. That man has a way of making the cello sound like a crying woman one minute, a laughing child the next. Listening to him, I’m always reminded of why I started playing cello in the first place – that there is something so human and expressive about it.

When the concert started, I peered at Adam out of the corner of my eye. He seemed good-natured enough about the whole thing, but he kept looking at his program, probably counting off the movements until intermission. I worried that he was bored, but after a while I got too caught up in the music to care.

Then, when Yo-Yo Ma played ‘Le Grand Tango’, Adam reached over and grasped my hand. In any other context, this would have been cheesy, the old yawn-and-cop-a-feel move. But Adam wasn’t looking at me. His eyes were closed and he was swaying slightly in his seat. He was lost in the music, too. I squeezed his hand back and we sat there like that for the rest of the concert.

Afterward, we bought coffees and doughnuts and walked along the river. It was misting and he took off his suit jacket and draped it over my shoulders.

‘You didn’t really get those tickets from a family friend, did you?’ I asked.

I thought he would laugh or throw up his arms in mock surrender like he did when I beat him in an argument. But he looked straight at me, so I could see the green and browns and grays swimming around in his irises. He shook his head. ‘That was two weeks of pizza-delivery tips,’ he admitted.

I stopped walking. I could hear the water lapping below. ‘Why?’ I asked. ‘Why me?’

‘I’ve never seen anyone get as into music as you do. It’s why I like to watch you practice. You get the cutest crease in your forehead, right there,’ Adam said, touching me above the bridge of my nose. ‘I’m obsessed with music and even I don’t get transported like you do.’

‘So, what? I’m like a social experiment to you?’ I meant it to be jokey, but it came out sounding bitter.

‘No, you’re not an experiment,’ Adam said. His voice was husky and choked.

I felt the heat flood my neck and I could sense myself blushing. I stared at my shoes. I knew that Adam was looking at me now with as much certainty as I knew that if I looked up he was going to kiss me. And it took me by surprise how much I wanted t

o be kissed by him, to realize that I’d thought about it so often that I’d memorized the exact shape of his lips, that I’d imagined running my finger down the cleft of his chin.

My eyes flickered upward. Adam was there waiting for me.

That was how it started.

12:19 p.m.

There are a lot of things wrong with me.

Apparently, I have a collapsed lung. A ruptured spleen. Internal bleeding of unknown origin. And most serious, the contusions on my brain. I’ve also got broken ribs. Abrasions on my legs, which will require skin grafts; and on my face, which will require cosmetic surgery – but, as the doctors note, that is only if I am lucky.

Right now, in surgery, the doctors have to remove my spleen, insert a new tube to drain my collapsed lung, and stanch whatever else might be causing the internal bleeding. There isn’t a lot they can do for my brain.

‘We’ll just wait and see,’ one of the surgeons says, looking at the CAT scan of my head. ‘In the meantime, call down to the blood bank. I need two units of O neg and keep two units ahead.’

O negative. My blood type. I had no idea. It’s not like it’s something I’ve ever had to think about before. I’ve never been in the hospital unless you count the time I went to the emergency room after I cut my ankle on some broken glass. I didn’t even need stitches then, just a tetanus shot.

In the operating room, the doctors are debating what music to play, just like we were in the car this morning. One guy wants jazz. Another wants rock. The anesthesiologist, who stands near my head, requests classical. I root for her, and I feel like that must help because someone pops on a Wagner CD, although I don’t know that the rousing ‘Ride of the Valkyries’ is what I had in mind. I’d hoped for something a little lighter. Four Seasons, perhaps.

The operating room is small and crowded, full of blindingly bright lights, which highlight how grubby this place is. It’s nothing like on TV, where operating rooms are like pristine theaters that could accommodate an opera singer, and an audience. The floor, though buffed shiny, is dingy with scuff marks and rust streaks, which I take to be old bloodstains.

Girl Wonder and the Terrific Twins

Girl Wonder and the Terrific Twins Betsey Biggalow Is Here!

Betsey Biggalow Is Here! Dangerous Reality

Dangerous Reality Knife Edge

Knife Edge The Stuff of Nightmares

The Stuff of Nightmares Operation Gadgetman!

Operation Gadgetman! Checkmate

Checkmate Love Hurts

Love Hurts Boys Don't Cry

Boys Don't Cry Cloud Busting

Cloud Busting Pig-Heart Boy

Pig-Heart Boy The Deadly Dare Mysteries

The Deadly Dare Mysteries Girl Wonder to the Rescue

Girl Wonder to the Rescue Noble Conflict

Noble Conflict The Monster Crisp-Guzzler

The Monster Crisp-Guzzler Betsey Biggalow the Detective

Betsey Biggalow the Detective Trust Me

Trust Me Nought Forever

Nought Forever Betsey’s Birthday Surprise

Betsey’s Birthday Surprise Dead Gorgeous

Dead Gorgeous Jack Sweettooth

Jack Sweettooth Crossfire

Crossfire Girl Wonder's Winter Adventures

Girl Wonder's Winter Adventures Whizziwig and Whizziwig Returns Omnibus

Whizziwig and Whizziwig Returns Omnibus Double Cross

Double Cross Hurricane Betsey

Hurricane Betsey Fangs

Fangs Tell Me No Lies

Tell Me No Lies Chasing the Stars

Chasing the Stars Hacker

Hacker Snow Dog

Snow Dog A Dangerous Game

A Dangerous Game Space Race

Space Race Whizziwig and Whizziwig Returns

Whizziwig and Whizziwig Returns A. N. T. I. D. O. T. E.

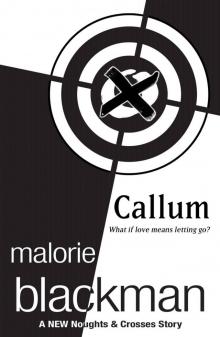

A. N. T. I. D. O. T. E. Callum: A Noughts and Crosses Short Story

Callum: A Noughts and Crosses Short Story